It is after business hours in Boston’s cavernous City Hall, but down an escalator, past shuttered service windows and darkened offices, the day’s activity is just beginning. Fifteen high school students have gathered in a room, grabbed pizza slices, opened laptops and are preparing to spend the next two hours deciding how to spend a million dollars.

Anthony Cardarelli, 15, drops his backpack and takes a seat. He is a newcomer at the meeting, and only came because his mother thought it was a good idea. He is soon startled to hear that the meeting will help allocate real city money, for real projects. “I thought it would be a simulation,” Carderelli says. “now I have to be a thousand times more serious!”

The teens are part of Boston’s Youth Lead the Change initiative, a participatory budgeting programme that draws young people firmly into annual cycles of municipal decision-making. This year, a two-month phase of public crowdsourcing has generated more than 700 ideas. Now committees of “change agents” like Cardarelli are working to distill those ideas to a few feasible proposals. In May, there will be a public vote, open only to Bostonians from 12-25, to choose which proposals get the green light.

Participatory budgeting has been used in one form or another in an estimated 1,500 cities worldwide since it first started in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 1989. But Boston’s is the first for youth only. The programme began under former mayor Thomas Menino and came to fruition after Martin Walsh assumed the office in 2014.

“It’s a truly transformative process for these young people,” said former White House advisor Hollie Russon Gilman on a recent panel at Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, who has written about participatory budgeting. “I joke that they come in for the pizza, but they stay because they’re amazed that they actually have decision-making power.”

Participatory budgeting (or PB) in the US is often aimed at groups that are traditionally marginalised, with youth being just one, Russon Gilman noted. “There have been huge outreach campaigns in low-income communities,” she says. “PB voting has included non-citizens. It is widening the pool of who can vote in the political process.”

Boston has a strong tradition of involving young people in city government, says Shari Davis, an energetic 28-year-old who climbed the ranks of city government through a series of youth opportunities and summer jobs starting when she was 15 and has led Youth Lead the Change from its inception. Davis notes that in the programme’s first year, 1,500 young people cast votes at polling places in schools, community centres and transit stations across the city. The next year, it was 2,000. In total, she estimates, more than 5,000 young people have been involved – whether submitting ideas, voting or working as change agents.

Project proposals selected for funding have included park and playground makeovers, community “art walls”, laptops for schools, water bottle refill stations and a feasibility study for a skate park. Some of the winning projects – including the Franklin Park playground improvements, which include designs to better serve children with disabilities – are currently under construction, but others have been completed. Thirty Chromebook laptops were delivered to high schools in three different neighbourhoods across the city, while the Paris Street Playground in East Boston has received its “extreme makeover”.

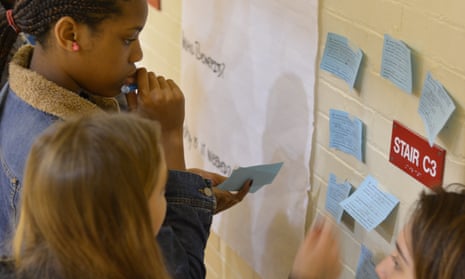

The change agents hail from many different high schools, neighbourhoods and backgrounds. They work in pairs, poring over printed pages of raw ideas. Some entries are overly grand (“Fix the transit system”); a few are silly; and a good number are not even eligible for the youth-controlled capital funds, which must go toward physical infrastructure or technology.

They discuss, ask questions and rate ideas in a shared online spreadsheet. Which is the greater need – heated bus stops or a more frequent bus service? Is bus service even under the city’s control? (No, but bus stop shelters are.) One group discusses renovating an ice rink and improving WiFi access on buses. Why WiFi? Because teens without a computer or internet access at home often write their compositions on smartphones as they journey to and from school. Free WiFi helps them avoid big data use bills.

Youth Lead the Change has already garnered attention and honours. It made the shortlist of 15 finalists for the 2014 Guangzhou International Award for Urban Innovation. And Seattle has recently launched a youth programme modelled closely after Boston’s. “This is an experiment in democracy. The young people have a real say over something they can point to in their community,” Davis says. “Those elements of real community change, real empowerment, make it applicable in communities all over the world.”

Participatory budgeting does have costs and risks. Beyond the $1m of capital funds, the city spends $100,000 for staffing, consultant fees and materials. Logistics can be complicated, even for finding meeting times and locations that suit high schoolers’ schedules and transportation options. And Davis stresses that the involvement of city officials is required for educating and advising the youth on budget processes.

What’s more, the notion of delegating spending authority to young people sparked doubts. Davis says there was initial scepticism from city officials about the appropriateness of ideas, and from the participants that they would truly be given a voice.

“It was very new and novel to all of us,” Davis recalled. “I would walk into a community centre and say, ‘I have a million dollars …’ and they would say, ‘Yeah, right.’ I believe in youth voice and assets, but even I didn’t understand how this would work.”

A pilot year evaluation showed that young participants reported personal benefits from their involvement, including heightened awareness of community needs and government processes, and new skills such as patience and teamwork. The evaluation noted some challenges, including insufficient time for thorough vetting of ideas, and in some cases disillusionment when certain projects did not win out.

Youth Lead the Change has continued to grow more youth-led, Davis notes, which has perhaps alleviated some early shortcomings. While adult facilitators ran the meetings in the first year, now the city hires and trains youths for that role, seeking facilitators who speak the languages of today’s Boston teens, including Cape Verdean, Spanish, Haitian Creole and Somali. And once proposals are funded, Davis works to keep youth involved in project design and implementation.

Facilitator Stephen Lafume, 17, joined Youth Lead the Change in 2014. He was the only student to accompany Davis to a national participatory budgeting convening in Washington, DC hosted by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, Harvard’s Ash Center and the Democracy Fund. “That was really cool,” he says. “I got to meet people from all over the country who are trying to make their communities better. This made it clear: government is not just the politicians, it’s about the people.”

Reflecting on Youth Lead the Change, Lafume says his favourite project was the skate park feasibility study. Even though there’s no plan to build it yet, he feels proud to have been part of that idea, as well as improvements to city playgrounds and parks providing accessible play structures for children with disabilities. “I can say I was part of that,” he says. “I’m seeing the change I put in my community.”

This article is part of the special Guardian Cities collaboration with the Young Urbanists and was commissioned by Victoria Pinoncely. Check out other stories from the collaboration on Twitter at #GuardianYU

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion