The remote Nepalese mountain village where Dr Nama Budhathoki was born was a full day’s hike from the nearest road. He attended the village school and spent his spare time herding goats and helping out on the family smallholding.

There were no computers - there wasn’t even electricity. It was only when Budhatoki, who would eventually become a leading digital disaster response expert, began studying in Kathmandu as a teenager that he even learned that computers existed – mostly through films. Convinced he’d seen the future, he applied for a degree course in computer science – before he’d ever seen a computer himself.

It was a hunch that changed his life. It got him a degree, a government job back home – and a PhD place in America. His focus: crowdsourcing and the capacity of digital technology to empower ordinary people.

In 2010, while in the US, his life changed again. On 12 January, a 7.0 earthquake hit Haiti. Among the responders was an new generation of humanitarians: digital activists and mappers, who crowdsourced expertise around the world to compile maps of the city and the needs of survivors after the quake. It was the first time professional responders – or Budhathoki - had seen anything like it.

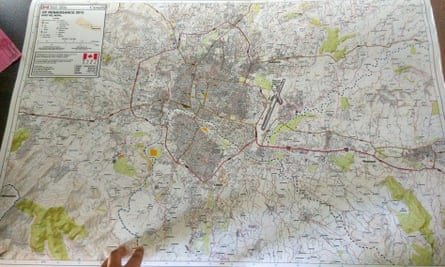

The idea that mapping is crucial to crisis response isn’t new. But mappers face serious problems. Existing maps may be crude and outdated – assuming they exist at all. Then, of course, is the fact that disasters like earthquakes literally rewrite the geography.

Crowdsourced mapping has changed all this. Now, maps are being built by citizens, Wikipedia-style. From volunteer specialists converting satellite images to online maps in their spare time to locals out in their neighbourhoods collecting GPS coordinates, this online community – led by Open Street Map - has been collectively mapping, with incredible detail, cites and countries, many for the first time.

“It’s revolutionary,” says Gisli Olafsson, humanitarian adviser for technology-led NGO consortium Nethope. “Even countries like Iceland have better maps as a result.”

And when a crisis hits, this online community, now thousands-strong, can do this against the clock. As a result, says Olafsson, mapping has become something that takes hours rather than weeks.

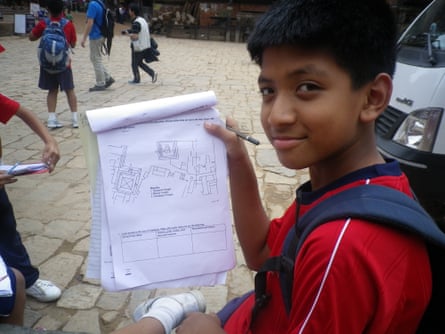

Watching the Haiti response unfold from afar, Budhathoki had an idea: “I started to speculate – what happens if there is an earthquake in Nepal? Could we do the same thing?” And could they build maps in advance? Returning to Nepal, he founded citizen mapping initiative Kathmandu Living Labs (KLL) and set about recruiting Nepali volunteers to tackle the massive task of mapping the densely populated Kathmandu valley.

The test of KLL’s work came, tragically, very quickly. On 25 April 2015, the plates beneath the Kathmandu valley began to shift. Budhathoki himself was at home with his family: he, his wife and children escaped their swaying house. With aftershocks every few hours, they were pitching tent in the grounds of nearby school when one of his KLL colleagues showed up. Now his family were safe, it was time to get to work.

“We began working in the parking lot,” he says, “it was too risky to go inside our building. We didn’t think too much. We just started mapping.”

The response exploded: within days, Budhathoki was at the centre of a worldwide team thousands strong. Global volunteers worked from satellite images to update his team’s pre-quake research. His staff scraped images of damage from social media and walked the streets of Kathmandu. KLL’s maps, better by far than any provided by officials, attracted the attention of first local responders and the Nepalese military, then MapAction and the UN. To a greater extent these organisations became dependent on KLL data. “The value was massive because the map quality improved literally overnight,” says data manager Andy Kervell, who volunteered with MapAction in Nepal.

Nepal was the first emergency in which a local group took such a lead role. Traditionally, mapping work, along with data collection, needs assessments and analysis, has all been done by governments and big international agencies. But the digital revolution, says Budhathoki, means local groups like his are now able to demonstrate why they, not the outsiders, should be in the driving seat.

“Of course we need support from people outside,” he says. “But without the local group, coordinating at the local level, identifying priorities – the people from outside don’t know what is needed. We had the language, the cultural knowledge. A disaster is a local phenomenon.” Olafsson agrees: “In some places a village or street might have several names depending on dialects ... That’s not something you can see from a satellite.”

One thing both Budhathoki and groups like MapAction agree upon: the crowdsourcing phenomenon is fundamentally changing disaster response. “This is a completely different model – now there is the ability to put it out to the crowd. I think it will go from strength to strength,” says Kervall.

It isn’t a magic bullet for mapping or anything else, he points out: data still has to be “cleaned” and verified. But for Budhathoki, it’s the ability to pool knowledge that’s really revolutionary. “It’s about collective intelligence. Local and remote mappers contributing to a single project, learning from each other, supporting each other – it’s a different way of organising human talents and knowledge ... It’s something we couldn’t even imagine 10 or 20 years ago.”

To see this in action right now, look no further than Ecuador, hit by a massive 7.8 earthquake just last Saturday. Within hours of the quake, Humanitarian Open Street Map Team activated a response, and hundreds of mappers began building the picture of the post quake area. Among the first to mobilise were the KLL volunteers, now experts in post earthquake digital mapping. “They felt very deeply the responsibility to help,” says Nama, who is himself advising the global OSM response, feeding lessons learned from last year back into the system.

Now the aid system needs to adapt. “What happened in Nepal was not something the formal humanitarian system had dreamed of,” says Budhathoki. “We need to start a major conversation with humanitarian actors, big organisations, governments.”

But his biggest frustration? That the buzz around KLL has not yet translated into concrete support. After the quake, KLL failed to raise the $50,000 it needed to continue. He doesn’t want to complain, but its biggest problem is a very traditional one: lack of cash.

Budhathoki says he thought the big organisations that used their data would step forward – but it hasn’t happened. “If we could get a very tiny fraction of the amount that humanitarian organisations spend, we could scale this up and take it to a very different level ... Nepal is waiting for the next disaster – why are we wasting time?”

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow@GuardianGDP on Twitter.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion