Noisy environments can be bad for both our mental and physical health.

One in five people in Europe are exposed to levels of noise considered harmful to health.

It is an environmental threat we don’t often see making headlines but, according to the European Environment Agency (EEA), this invisible form of pollution is one that we should be worried about.

Traffic noise is described as a “major environmental problem” which affects millions of people in Europe every year. The EEA estimates that long term exposure to noise, like busy traffic, railways and aircraft buzzing overhead, causes 12,000 premature deaths every year in Europe alone.

Noise is bad for our blood pressure, can make us vulnerable to heart attacks and perhaps most obviously in our daily lives, has a negative impact on our wellbeing and mental health. A study published this week by the University of Oxford even found a connection between increased levels of traffic noise over long periods of time and obesity.

The effects of noise pollution are particularly bad at night. If you find yourself tossing and turning in bed as cars, delivery mopeds and tendrils of bad 80s music drift through your window, you are not alone. Six and a half million people in Europe suffer from chronic sleep disturbance because of the noisy environments they live in.

Despite legislation introduced in the EU to try and reduce the number of people exposed to these unhealthy levels of noise, another EEA report earlier this year found that there had been no significant reduction in levels since 2013.

We are currently in the ‘anthropause’

At least, that was the case until COVID-19 hit and we entered a period scientists are calling “the anthropause”. Early on in lockdown, seismologists measuring the vibrations of the earth to detect earthquakes and erupting volcanoes reported that human-generated noise was at its lowest level in recorded history. From January onward, a wave of quiet spread across the globe as countries went into lockdown.

Suddenly, without the hustle and bustle of humans, we could hear birdsong even in the busiest city centres. Research by the University of Cumbria in the UK found that the ability to finally hear nature over the noise has made us love it all the more. When asked about their experiences of life during the pause, 94 per cent of the study’s participants said that listening to birdsong had led to them noticing nature more than they ordinarily would.

One particularly poignant response came from someone who said:

“[I] could hear all the birdsong while my baby was kicking in my stomach, [I] felt very peaceful and ‘part of nature’ at that moment.”

It seems we have developed a greater appreciation for quiet after seeing the benefits it has had for ourselves and the natural world. With life slowly returning to some semblance of normal and noise starting to creep back in, now begins the challenge of carrying through this quiet into our everyday lives.

Quiet Parks International

Gordon Hempton is an acoustic ecologist who has circled the globe three times in search of nature's rarest sounds - which can only be found where there is no manmade noise.

Now he is on a mission to “save quiet”. Hempton tells me the reason noise pollution can have such a big impact on our health is because it drowns out all those important auditory cues that let us know we aren’t in danger. “Since you can’t hear these faint sounds, you are in a threatening environment. In the presence of noise pollution, you can’t feel secure.”

But, says Hempton, “Quiet is the antidote to noise. Quiet is transformative.” Transformative not just for us, but also for ecosystems too.

“When we go to the very few quiet places that are left on earth, we find incredible biodiversity,” he says, adding that thanks to this biodiversity and overall better environmental health, they also sequester more carbon.”Those few remaining quiet places are saving our world.”

He set up Quiet Parks International (QPI) with co-founder Vikram Chauhan, to quantify the value of quiet places by providing “pristine and endangered” areas with an award.

So far they have established the world’s first Wilderness Quiet Park on the Zablo River in Ecuador which both recognises the sustained absence of noise pollution in the area and gives it recognisable value through tourism. It is hoped that this added value will prevent the development of the land which would pollute the quiet as well as providing a sustainable income for the Indigenous Cofán people who live there.

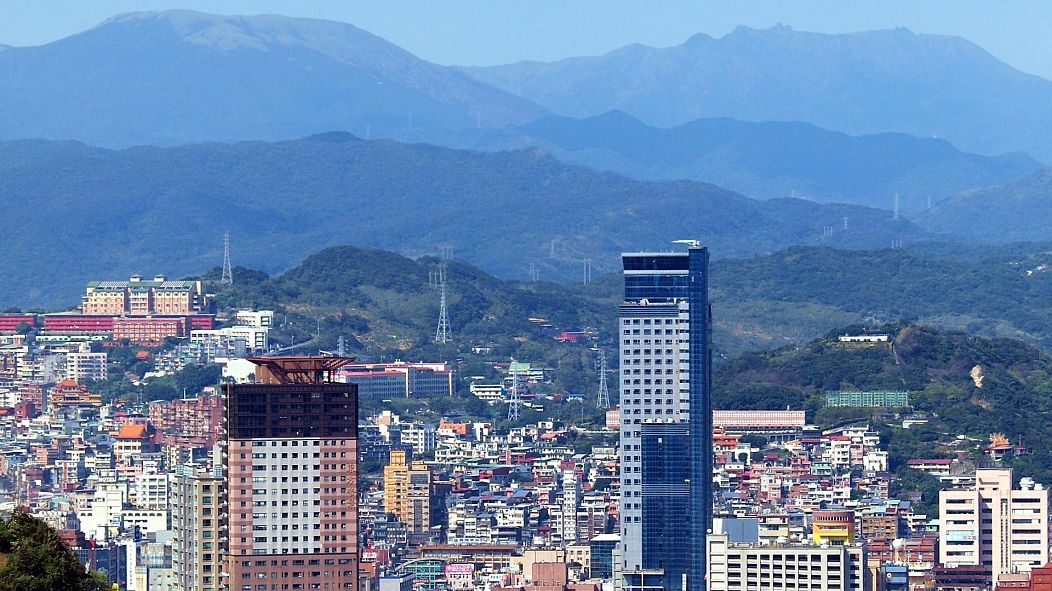

Quiet places don’t always have to be wild, however. QPI has also set up certification for spaces in more densely populated areas. In June the NGO gave Yangmingshan National Park in Tapei, Taiwan, one of the world’s most polluted cities, its first Urban Quiet Park award.

Urban quiet is a bit different to that in the wilderness - Hempton acknowledges that these spaces will never be free of noise in the same way. Instead of using uninterrupted periods of quiet to measure these places, as they do for the Wilderness Parks, the judgements about noise levels for urban spaces are cultural.

“This means that when you experience quiet in Stockholm, for example, you are experiencing the quiet of the Swedes,” explains Hempton. The awards will be used in a similar way, by using quiet as a reason for people to visit, it prevents these valuable oases of calm from being absorbed by the noisy city.

On the organisation's website, people can nominate spaces they believe deserve an award. As soon as the global pandemic will allow, there are a number of locations across Europe, including some in Poland and Sweden, that the team are hoping to assess and award.

Hush City

How we perceive quietness isn’t just about the measurement of noise - and not all sounds are necessarily damaging pollution. Dr Antonella Radicchi, an architect and urban planner in Berlin, created Hush City, to allow people to record their own feelings about the sounds they hear around them.

It’s a free citizen science app which gives people the ability to assess the auditory quality of their local area. Hush City aims to empower people to identify quiet areas in their own neighbourhoods by encouraging them to map soundscapes. Quiet spaces are not listed based on an abstract decibel level but instead “identified and evaluated by the citizens, according to their preference and lifestyle”

The app’s creators say that while traditional examples of quiet places “include huge parks and big green areas” it is important to take into account people’s opinions and feelings about where they like to spend a peaceful moment.

“Small, quiet spots embedded in our neighbourhoods, at a walking distance from the places we work and live need to be identified and protected,” they say.

The resulting map is a worldwide, crowdsourced directory of quiet places recorded by the app’s users. To record a peaceful place close to you all you have to do is download the app, go to your favourite quiet spot, and select the “Map the quietness around you” option.

Hush City will record the “soundscape” using your phone’s microphone, and you can then add a picture and answer a few questions about the quality of the place you have recorded. Once submitted, this information is shared with the app’s users around the world.

So far it is being used by city councils in Berlin, Germany and Limerick, Ireland to create Quiet Areas Plans. If quiet mapping became the new norm, it would help preserve those secret peaceful spots around the city, and in turn, give us a break from the cacophony of noise pollution we are exposed to every day.