Spring flowers are always a welcome sight, but not when the winter season still has its grip on a region. Throughout February and March, nature lovers in Pittsburgh and throughout southwestern Pennsylvania have noticed the premature flowering of seasonal plantlife, as temperatures have oscillated wildly between sunny, warm days and bitter, snowy cold spells.

Dr. Benjamin Lee, a postdoctoral research associate and ecologist at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, expresses concern over seeing flowers on recent walks through his neighborhood, knowing that they could become vulnerable to sudden dips in temperature.

“There's a chance that if plants flower too early, and then there's a frost event, that frost event can kill them, or, at least, damage them to the point that they're not able to reproduce that year,” Lee tells Pittsburgh City Paper. “And that's obviously not good for them. It's not good for these natural populations and being able to maintain those.”

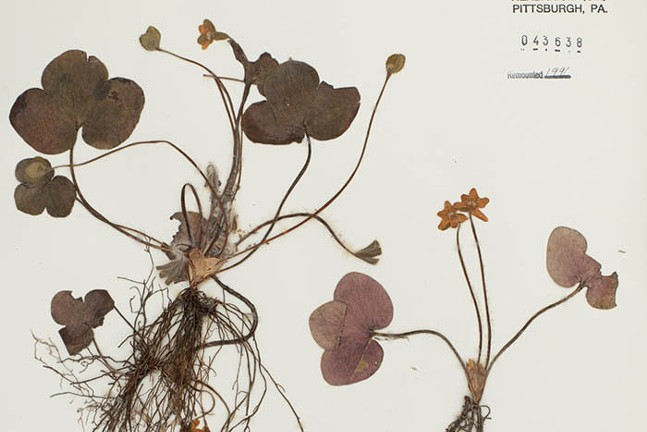

Lee, along with fellow researchers from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and around the world, released a study in December 2022 warning of the risks posed to North American ephemeral wildflowers. Published in the Nature Communications science journal, the study surveyed data from 5,522 individual specimens collected from 1901 to 2020, representing 40 species from Asia, Europe, and North America.

The study, for which Lee served as the lead author, expands on the work of naturalist and author Henry David Thoreau, using historical observations dating back almost 200 years.

“He was specifically looking at differences in wildflower phenological sensitivity, so, the rate of change of flowering time in response to warming, and comparing wildflowers to trees in that respect,” Lee says of Thoreau, best known for his 1854 proto-environmentalist book Walden. “So, very similar to the study that we just published.”

As expected, however, there are discrepancies between Thoreau’s research and the recent study. “The main difference between the two of them is that in the previous study, obviously, Thoreau wasn't moving around too much. He's famous for being like a pseudo-hermit up in Walden Pond in Massachusetts. So, all of his observations are from that one, very localized region.”

Lee says the latest study focused on spring ephemerals, or flowers active for about a month in the “really early spring.” He adds that these plants rely on “access to elevated light availability” in order to survive for the rest of the year.

“It would be like if you went home for the holidays and ate all of the calories that you needed to survive the rest of the year, and then just slept it off,” he explains.

Any lack of light caused by climate change results in a sort of starvation for these plants. “They have this really specialized strategy where they really need to make the most of this access to light early on in order to gain enough carbon to grow, survive, and reproduce … And so, this group of plants is going to be particularly vulnerable, we think, in response to climate change.”

While the study looks at this issue globally, Lee says western Pennsylvania, and the surrounding Appalachia region, in general, has a “really large richness” of spring ephemeral wildflower species. A reduction in their populations could have serious consequences beyond just eliminating pretty pops of color to the landscape.

“These wildflowers often provide some of the earliest resources in spring to pollinators,” he says, adding that insects like bees — another life form seeing the disastrous effects of global warming— rely on them for pollen. “And if there's a mismatch, where the plants aren't there, either because they're dying because of climate change, or because the timing is just off, that can be really problematic to maintain local pollinator networks.”

Consequently, he says, we should expect to see a reduction in biodiversity if this trend continues.

“And so, for biologists, at least those of us that sort of work in the field and focus on natural ecosystems, biodiversity is a huge focus for us because it's been linked to all of these different resources that we need in order to have healthy ecosystems and healthy communities and a healthy society,” he says.

He stresses the importance of trees when it comes to the survival of spring ephemerals, particularly what he calls “understory wildflower species,” which account for a “disproportionately large amount of the biodiversity in North American temperate forests.”

One major aspect of the study details how canopy trees in North America are “significantly more sensitive to spring temperatures.” As a result, trees that would usually stay bare in the early spring may leaf out before the wildflowers beneath them have a chance to soak up precious sunlight.

“The flowers are moving earlier as well,” says Lee. “So, both groups are moving earlier with warming temperatures. It’s just that, per degree Celsius of warming, the trees are moving faster. So, for every degree of warming it gets, the trees are moving ahead more in time compared to the wildflowers.”

He adds that understory wildflowers would typically come out three or four weeks before “the canopy closes,” or before the trees “fully leaf out.”

“As we're moving into warmer springs, that period of time is decreasing,” says Lee.

This dynamic could have major implications for the understory layer of wildflowers, which, according to the study, accounts for about 80% of plant species diversity in temperate forests worldwide and “provides a critical role in the functioning of these ecosystems.”

While the situation may seem dire, Lee says there are ways for individuals to make a difference. He recommends downloading and using iNaturalist, an app developed through a joint initiative of the California Academy of Sciences and the National Geographic Society. The app allows users to identify plant and wildlife species in certain areas.

The app serves as an educational tool and crowdsources information that scientists can then use in their research.

“It's a really incredible and useful tool,” says Lee. “It's also just fun for what it is. To me, it feels very similar to Pokémon GO, where you have this excuse to try to go out into nature and just walk around and see what you can find … But it's also a really important way that the layperson can help us collect data and can contribute to science.”

Lee cites another, more visible threat, particularly in the United States, that affects ephemeral seasonal beauties — lawns.

“That's the easiest way to kill off all of the biodiversity that you might otherwise have on your property, especially in urban areas, including around Pittsburgh,” he says. “You have reduced whatever diversity there was there in the plant life to grass, to one single species.”

Lee cautions against certain lawncare or landscaping practices, such as excessive mowing or using herbicides. He also wants the public to understand that not all native plants, particularly many essential to pollinators, are ornamental, and can even look “weedy.”

He adds that ecologists recommend everyone re-naturalize their approach to plants, whether that’s allowing your lawn to grow and flower, or, for Pittsburghers living in apartments, putting native wildflowers in a small outdoor planter.

If you’re in a more rural area and have access to a lot of land, he says the key is, “just being aware that these wildflowers are important, and trying not to disrupt them.”